Like all things Linux, there are a dozen ways to do anything, and dozens of how-to guides on how to do it wrong. System logging is no exception. Modern Ubuntu distributions use rsyslog, so this is a guide to setting up remote system logging between two modern Ubuntu machines.

System logging is the way that a computer deals with all the info and error messages generated by the kernel, drivers, and userland applications that should be saved in case they are useful, but aren’t generally immediately needed by the user. So generally the messages are sent to your locally-running rsyslog program, and saved to /var/log/syslog. Remote system logging is where one computer (computer Alpha) will send out all its system messages to a different computer (computer Beta), to be processed/stored there. This can be useful if computer Alpha (the log sender) is having hardware troubles and frequently crashing, making it nice to have a record of what happened in the final few seconds before the crash.

Changes on the log receiver (computer Beta)

Edit the file /etc/rsyslog.d/50-default.conf. Add these lines before any other non-commented lines in the file:

# let's put the messages from alpha into a specific file

$ModLoad imudp

$RuleSet remote

*.* /var/log/alpha.log

$InputUDPServerBindRuleset remote

$UDPServerRun 514

# switch back to default ruleset

$RuleSet RSYSLOG_DefaultRuleset

This loads the “imudp” module which allows us to run a UDP (not TCP) log receiving server. Then we set up a rule set that logs all logs to the file /var/log/alpha.log. We apply that rule set to the UDP server, and start the server on port 514. Then we switch back to the default ruleset, and the rest of the file tweaks that ruleset (where different types of messages end up).

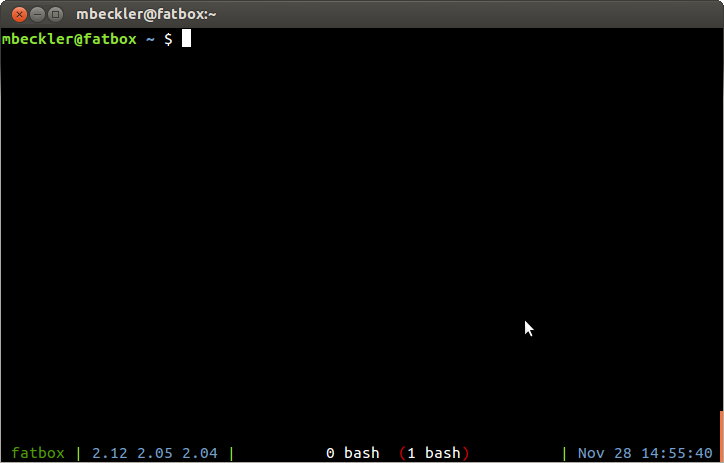

To apply the change, run “sudo service rsyslog restart”. You can use netstat to check which ports have listeners:

sudo netstat -tlnup

Which should produce a line like this:

udp6 0 0 :::514 :::* 27102/rsyslogd

Changes on the log sender (computer Alpha)

Edit the file /etc/rsyslog.d/50-default.conf. Add these lines before any other non-commented lines in the file:

# log all messages to this rsyslogd host

*.* @1.2.3.4:514

This tells rsyslog to send all messages (*.*) to the specified IP address via port 514. To apply the change, run “sudo service rsyslog restart”.

Test it out!

On the log receiver (computer Beta) run this command to watch the log file from alpha:

sudo tail -f /var/log/alpha.log

On the log sender (computer Alpha) run this command to put a silly message into the system log system:

logger Hello World

You should see something like this show up in the terminal on the log receiver:

Jan 10 17:56:53 alpha eceuser: Hello World

TCP instead of UDP

I initially tried to set up the log receiver to listed on a TCP port instead of UDP, but it just wasn’t working, and I’m not sure why.

If you wanted to do TCP instead of UDP you would change the lines for the log receiver configuration, and then use two @@ instead of just one @ in the log sender configuration.